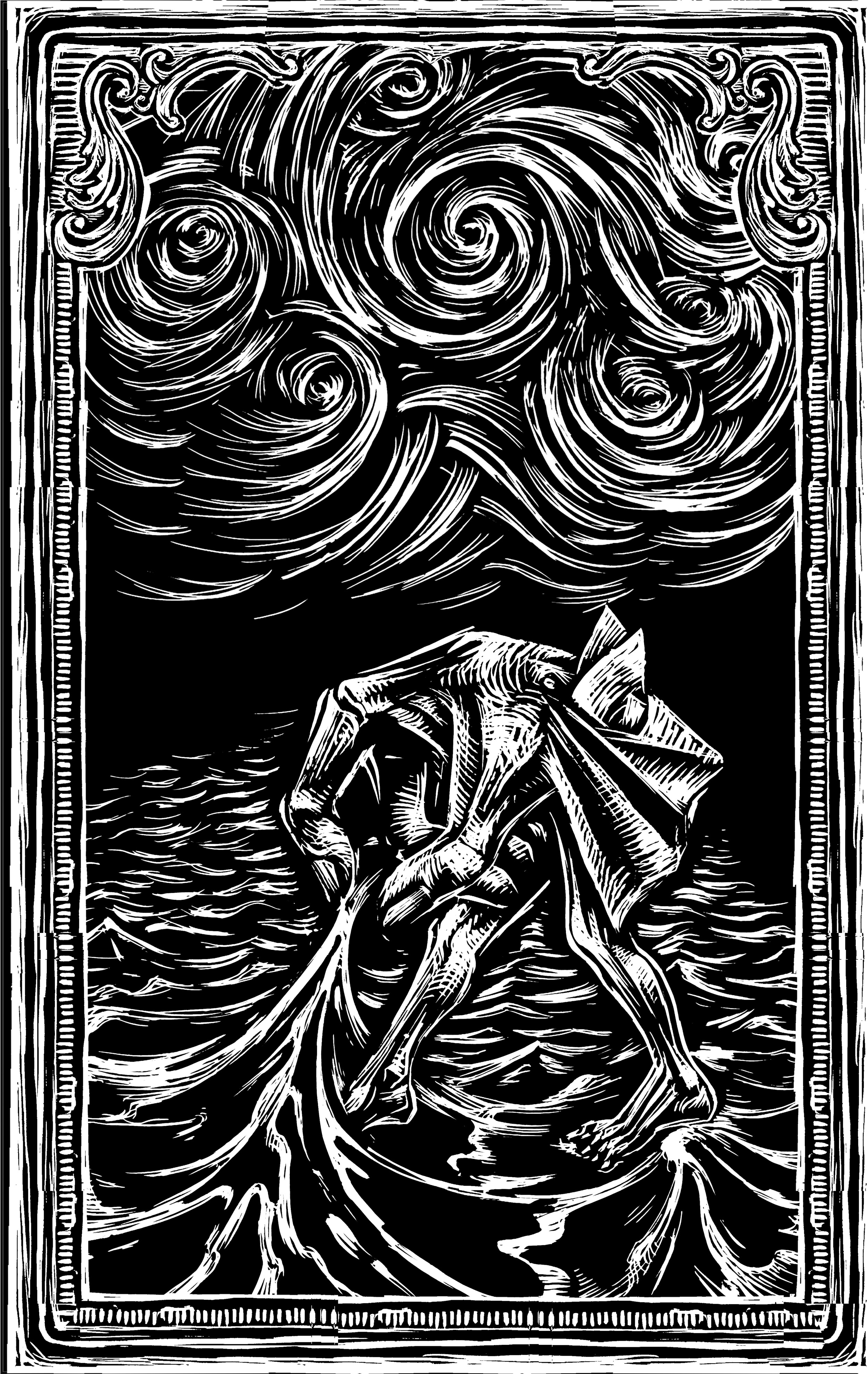

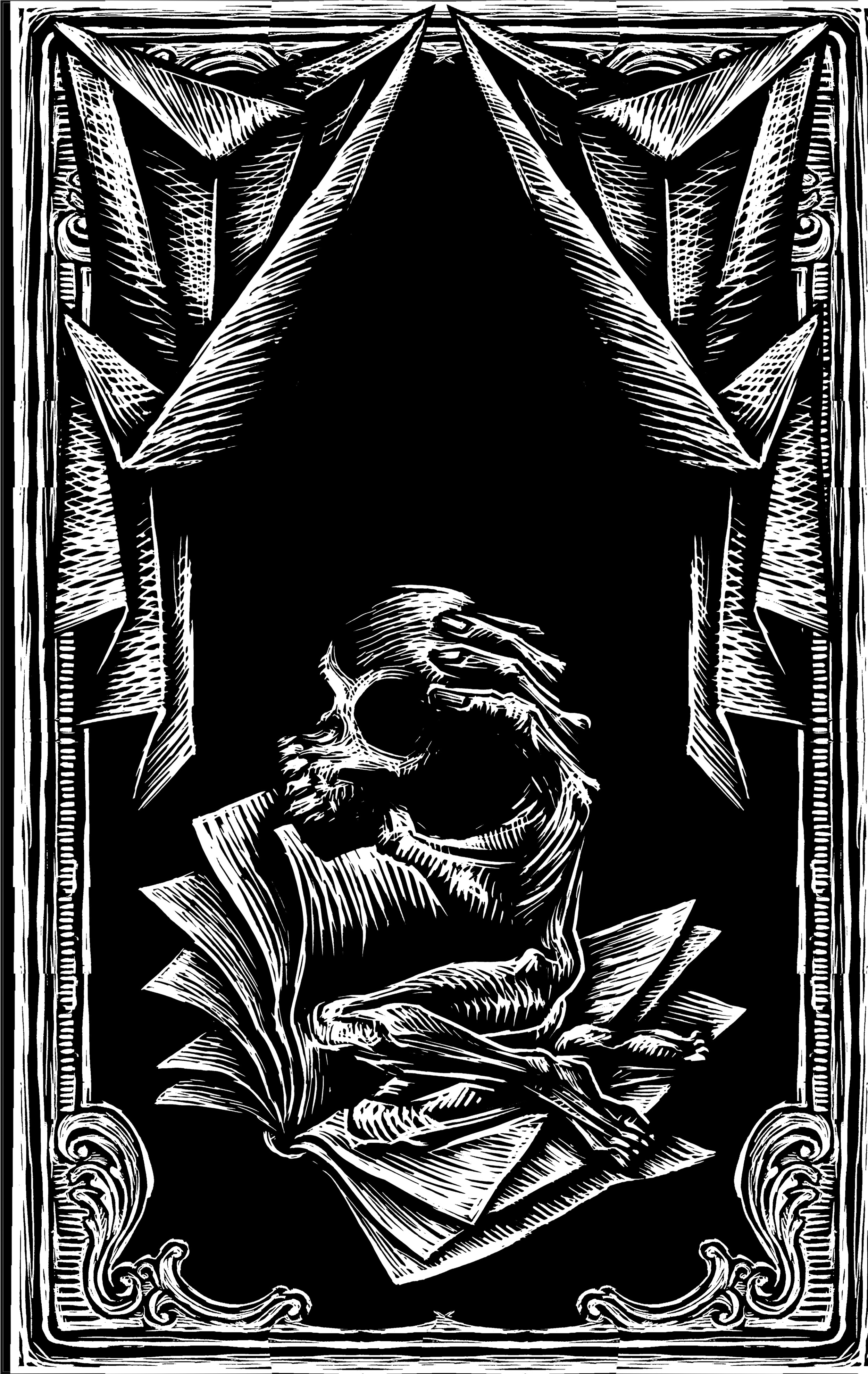

Lavishly illustrated by the Mexican artist Eko, the Restless Classics' 400th Anniversary Edition of Don Quixote launches on October 6. Get a sneak peek below of his 20 brilliantly original woodcut illustrations for the book.

“The anecdotes are inventions from the character’s fantastic imagination. They are attributed to madness because at that time creation was limited to theology. The creation in Don Quixote is an exercise of a pure creation that inspires us." —Eko

by Miguel de Cervantes

Translated from the Spanish by John Ormsby

Introduction and Video Lecture Series by Ilan Stavans

Illustrations by Eko

Newly introduced by leading Quixote scholar Ilan Stavans, this 400th Anniversary edition of Don Quixote of La Mancha—called the most popular book in history after the Bible and the first modern novel—inaugurates Restless Classics: interactive encounters with great books and inspired teachers. Each Restless Classic is beautifully designed with original artwork, a new introduction for the trade audience, and an online video teaching series led by passionate experts.

Paperback • ISBN: 9781632060754

Publication date: October 6, 2015

About the Artist

Born in Mexico in 1958, Eko is a cartoonist, engraver, and painter. His wood etchings, often erotic in nature and the focus of controversial discussion, are part of a broader tradition in Mexican folk art popularized by José Guadalupe Posada. He has collaborated on projects for The New York Times, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and the Spanish daily El País, in addition to having published numerous books in Mexico and Spain.