The horror, the horror….

We can all picture Frankenstein’s monster, but can we really conjure the dread and terror of Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus? A classic in its two-hundredth year of life, the masterpiece has indeed proved immortal, and is even more popular today than it was upon publication. But the popularity of the book has sometimes dimmed the horror of the original image: a man created from the salvaged anatomy of the recently buried dead.

The tempestuous tale of Frankenstein’s origins is almost as good as the resulting novel. Mary Shelley had just run away with the still-married poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, and her meddling stepsister, Claire, was along for the trip. This uneasy threesome met with Lord Byron, who had become Claire’s lover, and his physician, John William Polidori, at Lac Leman in Switzerland for the summer season. Cold and heavy rains (the consequence of an Indonesian volcanic eruption the year before) put a damper on their holiday. On Byron’s suggestion, the group resorted to telling ghost stories (and one presumes other amusements), with each member of the party charged with writing his or her own chilling tale. No inspiration came to Mary—until the vision for Frankenstein appeared in a dream, one so terrifying that she knew she had to replicate the sensation in her readers. This June, two hundred years after that fateful night, we’ll be releasing a very special edition of Frankenstein, the second book in our Restless Classics line.

The acclaimed novelist and critic Francine Prose, in her introduction to our edition, makes a compelling case for the continued relevance of this towering work of gothic fiction. Prose speculates that Mary Shelley was likely influenced not only by her dream and the stormy lakeside retreat, but also by her second pregnancy:

Mary was pregnant with Shelley’s second child, doubtless a source of anxiety since her first child, Clara, had died soon after birth and Mary’s own mother had died in childbirth. Little wonder, then, that the story Mary wrote would be so thoroughly steeped in violence, in grief, in loneliness and fear, in remorse and guilt.

Now, even as medical technology brings increased security to childbirth, its advances bring back to life the old questions Mary Shelley originally tangled with: "What is a human being? Is it dangerous to play god? What are the ethical implications and limits of scientific research?"

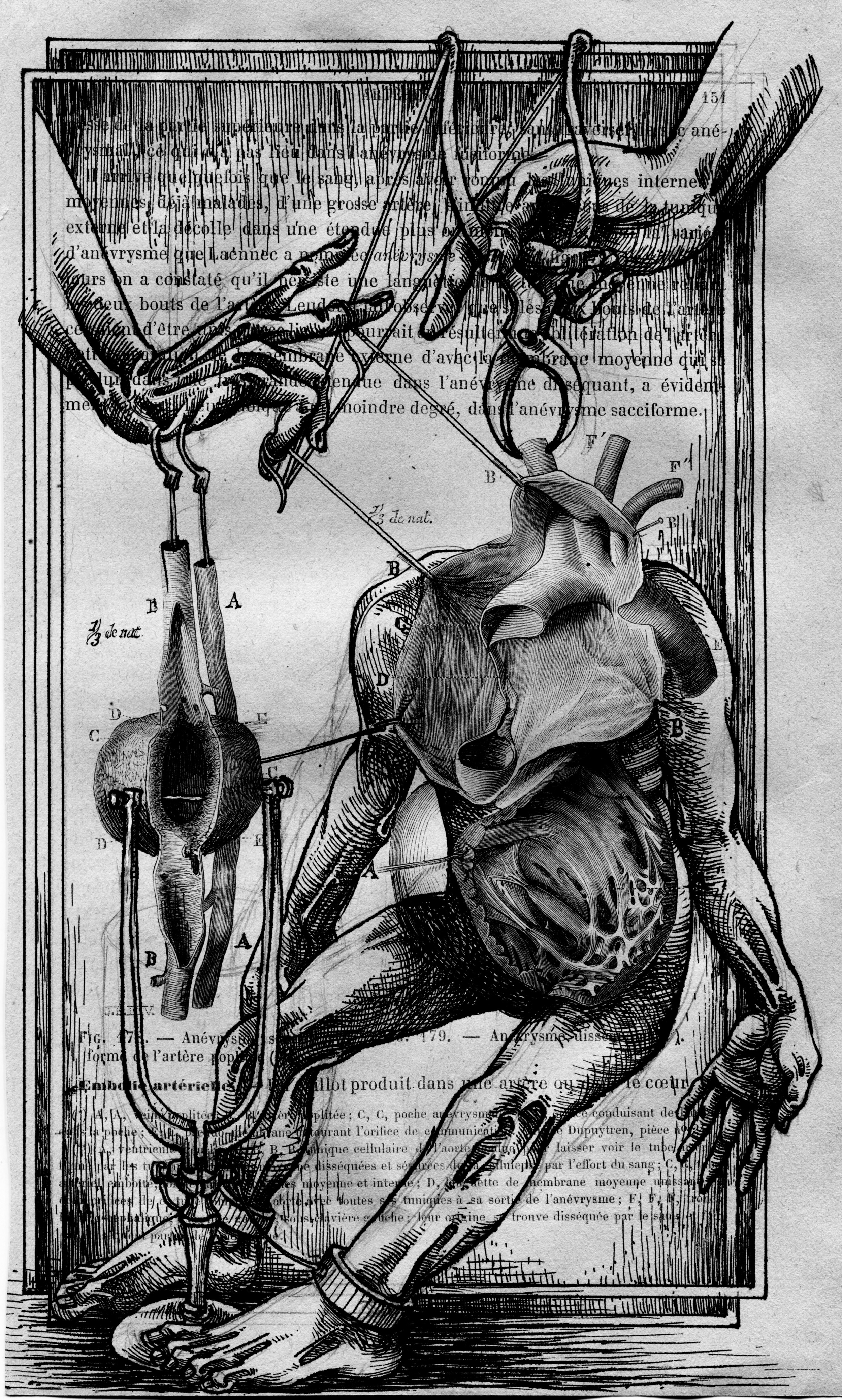

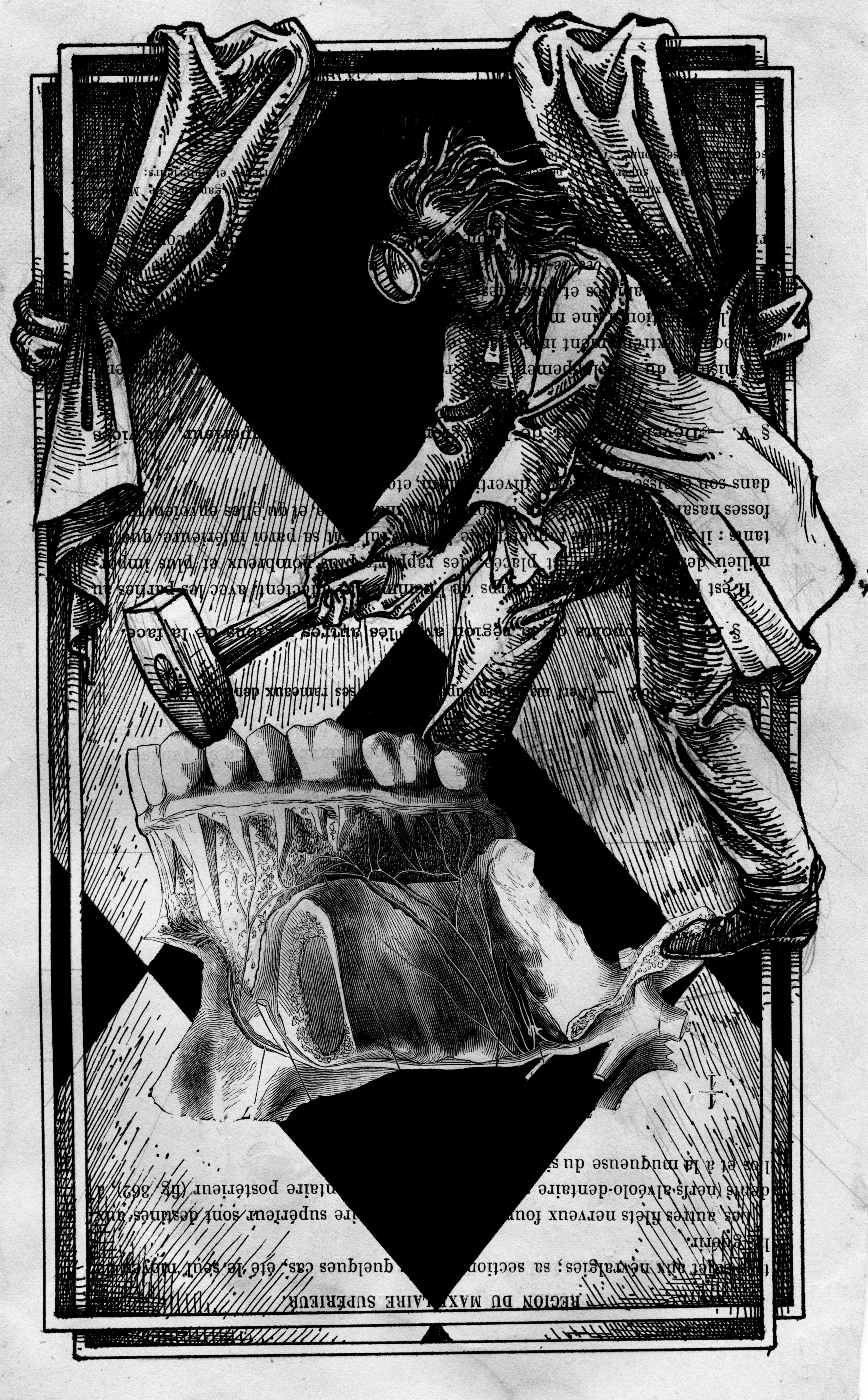

The delusion of reason: Eko illustrates Frankenstein

In tandem with Francine Prose’s introduction, the fiercely original Mexican artist Eko brings readers back the gothic horror of Shelley’s text with 26 original illustrations throughout the book. In his illustrator’s introduction, Eko writes:

The scientist Hippolyte Cloquet described writing his groundbreaking Treatise on Descriptive Anatomy “with scalpel in hand,” .... In this series of ink drawings I use as a base the pages of a French anatomy book from the period during which Mary Shelley wrote her novel; the paper is an artistic setting, historic and aesthetic, and the information and the forms of the letters are Dr. Victor Frankenstein’s laboratory. With my drawings I continue Dr. Frankenstein’s line of thinking and ask the same questions he asks: Is it right for science to create human beings? Is that “creature,” that “monster” the consequence of human arrogance? Is being familiar with anatomy enough to know what it means to be human? Francisco de Goya writes on one of his etchings, “The sleep of reason produces monsters.” This monster is formed with human parts and comes to life with the force of electric energy—but still isn’t human. It’s the product of dreaming, of a delirious mentality. He doesn’t even exist; he is the fear that we have of our own work. My drawings, like the mind of Dr. Frankenstein, start with the delusion of reason.

A sneak peek at 10 of Eko's original illustrations

Pre-order your copy of Restless Classics’ Frankenstein to read Francine Prose’s introduction, see all 26 of Eko’s illustrations, and reacquaint yourself with a timely 200-year-old masterpiece of gothic horror.