After a year of upheaval, protest, and loss, we want to celebrate the books that have brought us solace and joy.

The newly slowed pace of life gave many of us the chance to revisit old favorites, re-learning why we fell in love with personal touchstones like Walter Benjamin or Milena Michiko Flašar. Some of us immersed ourselves in brand-new worlds, escaping isolation with the help of wizards and detectives. And lots of us found the new views we needed in personal essays, history, and novels. Find all of our picks at your local bookstore or here on Bookshop.

With gratitude for the books (and cats) that kept us company this year, and for you,

The Restless team

Minor Detail by Adania Shibli, translated from the Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette, is one of the most moving and thought-provoking books I read this year. It’s a slim book, easy to read in one sitting, but it packs the emotional punch of a novel ten times its length and will stay with you long after you’ve finished it.

Nathalie Léger’s The White Dress, translated from the French by Natasha Lehrer, beautifully weaves together the true story of murdered performance artist Pippa Bacca and Léger’s fraught relationship with her own mother in a genre-blending mix of art criticism, research, memoir, and biography.

I couldn’t put down The Discomfort of Evening by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, translated from the Dutch by Michele Hutchison. Winner of the 2020 International Booker Prize, Rijneveld’s brutal depiction of grief, death, and loss is harrowing, to say the least, but their bold grappling with the shortcomings of religion and belief in the aftermath of tragedy is profound.

—Alison (Associate Editor and Grants Manager)

Like any English major trying to process the end of the world as we know it, this year I turned to the personal essay collection. Two standout favorites were A History of My Brief Body by Billy-Ray Belcourt and Something That May Shock and Discredit You by Daniel M. Lavery. Belcourt’s queer Cree reading of the conditions of embodiment is hauntingly beautiful, and plays with temporality in fascinating ways. Lavery takes a humor writer’s approach to the genre, articulating his gender transition by riffing off everything from medieval texts to original series Star Trek. I found myself wanting to underline every paragraph.

—Sasha (Intern)

Author debuts and personal nonfiction mark my favorite books this year. I count the fantastic first books I read as some bright spots of 2020. Sleepovers by Ashleigh Bryant Phillips, a really, really great short story collection, took up residence in my brain and has yet to leave. Phillips’ insight into her characters’ inner lives and grasp of voice is breathtaking. I loved the premise and form of Jenn Shapland’s memoir, My Autobiography of Carson McCullers, which is a great text for thinking about our relationships to the archive and authors we love, how their lives and stories shape our own, and what is left out when a life’s story is told. And then there is Luster by Raven Leilani, a truly phenomenal novel. Leilani has such a grip on her characters and plot and text, down the level of sentence. I was in awe of her craft, the way she spins long, sprawling sentences, how she drew me along through strange, visceral highs and lows.

As for the nonfiction, three books stand out. Reborn: Journals and Notebooks 1947–1963, the first volume of Susan Sontag’s personal notebooks, gave my brain a much-needed jumpstart somewhere around July. The essays in Alexander Chee’s How To Write An Autobiographical Novel continue to pop into my head at random moments, particularly his essays about studying with Annie Dillard, his activist work in San Francisco, and his time as a cater waiter in New York. And Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights, in which Gay recounts his own year-long daily practice of seeking delight. I continue to wax poetic about it to anyone and everyone who will listen.

—Mira (Intern)

Walter Benjamin in Paris © Gisèle Freund

Even in terms of my reading habits, this has been a most peculiar year. The fact that I haven't traveled has resulted in the gift of time. I become closer with old friends (Quevedo and Yeats, for instance) and have somehow forgotten about my contemporaries. In March, my personal archives (manuscripts, correspondence, and memorabilia) and book collection were acquired by the University of Pennsylvania, where they will be housed. Researchers I will never know, for reasons I don't care to imagine, will open them from now on. I spent from August to October packing 160 boxes. As I organized the material, I reopened some I hadn't looked at for years. Walter Benjamin, for instance. The rediscovery made me feel close to him; in fact, I realized, upon rereading some of his essays, that he has been a lighthouse for me in unsuspected ways. The same with Hannah Arendt. Conversely, I reentered Octavio Paz's oeuvre, which I thought was central to my thinking, and felt utterly disillusioned. In any case, I will remember 2020 as the year in which I deposited my 8,000-volume library in someone else's capable hands and, without anticipating it, became absolutely free.

—Ilan (Publisher)

Matt Damon in the 1999 film adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley

As lockdown descended I went for a claustrophobic read that had long lingered on my list: Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley. I’m convinced that Highsmith’s project was to create a thoroughly unlikeable character, and then make the reader obsessed with his every thought and action. One surprising thing to me was how miscast Gwyneth was in the (excellent, though quite different) movie: Marge in the book is heartbreakingly dowdy and depressed, and Ripley despises her for it. The book is a dark, mean masterpiece of violent male self-interest.

The single most beautiful book I read this year was a glorious escape: Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams, which was even more powerful upon a second reading. The book is so eerie and exquisite and particular it’s hard to describe; it’s like if Charles Portis and Cormac McCarthy had melded minds and then done enough acid that they reached some other, more poetic plane of consciousness. It’s the kind of book that makes it difficult to read another novel afterward, whose sentences will inevitably disappoint.

So, I read Hamilton. Yes, right after seeing the Disney+ online telecast—both so good! Among other things, the book is a welcome reminder that the people who shaped the country, while often misguided, were driven by complex and reasoned thinking—and reading.

—Nathan (Editor and Marketing Director)

Retreat from reality may well have been the best literary option this year, but for whatever reason, I rushed towards nonfiction.

Early in the year, I picked up Carmen Maria Machado’s 2019 memoir In the Dream House. I purchased it expecting a discussion of abuse that would satisfyingly buck normative, gendered narratives on the topic, and found a work far more complex and textured than my own thinking, which forced me to confront my own expectations of justice and of resolution.

I also found myself drawn to social theory and culture writing, and am currently reading Mark Fisher’s Ghosts of My Life. Right now, when meaningful political progress seems to be in limbo and even the most basic forms of government responsibility for public health have fallen by the wayside, Fisher’s concept of lost futures rings true, and provides a cultural framework for understanding, beyond mere despair.

Earlier in the summer, at the height of the BLM protests, I read Are Prisons Obsolete by Angela Davis and The End of Policing by Alex S. Vitale, both of which present the history of police and prisons in the United States in a way that provides tools for interrogating the criminal justice system at present.

And finally, I’ve been getting into speculative fiction, most recently Restless’s own English translation of Red Dust by Yoss. Where previously I had little interest in sci-fi and supernatural literature, this year, I found myself drawn to worlds other than our own as a way to make sense of an incomprehensible present. In our particular time of great upheaval, speculation may be the best tool we have.

—Annika (Intern)

The best book I read was The Corner That Held Them by Sylvia Townsend Warner, which I already talked about in our quarantine reads roundup. I peaked early this year, which is fitting!

I did also love Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis and can't recommend it highly enough, if the people in your vicinity won't mind you stopping every other page to read a sentence out loud to them. It's so funny, it's unfair.

And I thought that Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss was perfect. Sometimes it’s hard to feel fresh horror at gender-based violence; we’ve been swimming in it forever. Sarah Moss does something truly original with that problem, using the backdrop of a summer “experimental archeology” course reenacting life in Iron Age Briton. So yes, there’s plenty of fresh horror, as well as gorgeous nature writing, and characters who all feel fully alive, and even a hint of lesbian love. It’s also a great working-class novel—or novella, really. I can’t believe what the author managed to do in 130 pages.

—Christine (Assistant Publishing Manager)

The best book I read this year was hands down Return of the Thief, the final entry in Megan Whalen Turner’s Queen’s Thief series. First, to get it out of the way: yes, according to the publisher, this book was written for ages 13–17 (as in, high schoolers), but to dismiss the book (and the series) as another entry in the teen sword and sorcery pantheon completely misses the point.

I began reading Whalen Turner over ten years ago (I found the first book in her series, The Thief, in the Philadelphia Free Library), which is much later than many of her other fans who started reading back in 1996. Return of the Thief, and the whole series really, deals with mythmaking, disability, and politics, all set in a world loosely based on the ancient Mediterranean. More than that, the series is consistently exciting and clever with stunning revelations that force multiple re-reads. The final book was both engrossing and satisfying — the perfect companion to staying at home this year.

—Arielle Kane (CFO)

This year, I spent most of my time exploring stories by authors from Latin America and Asia, and specifically by women authors. I read a Restless title The Body Papers by Grace Talusan in January. The intersection of cultures from the East and West makes it a meaningful throwback for me. Lake Like a Mirror by Malaysian author Ho Sok Fong, translated from the Chinese by Natascha Bruce, and Bluebeard’s First Wife by Ha Seong-Nan, translated from the Korean by Janet Hong are two haunted, gripping short story collections that vividly depict feminine identity and its role in both cultural backgrounds’ day-to-day life.

Sexographies by Gabriela Wiener (translated by Lucy Greaves and Jennifer Adcock) completely blew my mind. The voice of the story is daring, and it’s one of the most courageous and creative ways to bring spotlight to femininity. As a big fan of Samanta Schweblin, I read Little Eyes (trans. Megan McDowell) this year, and was taken with the cultural diversity it weaves into the narrative. I felt like I was traveling all over the world with the shift of the character perspectives. My most recent, yet possibly my favorite book this year, is Stories of the Sahara by Taiwanese author Sanmao. It’s another book about traveling, but I think what makes the book so unique is how it’s about a woman traveling around the Sahara desert, interacting with a culture completely unknown to her. I find solace in reading this book while not being able to travel as I wish, and I definitely recommend reading more translated literature, especially books written by authors whose cultural backgrounds we’re less familiar with.

—Jenna (Intern)

The novel that affected me the most this year was Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. I’m usually not a re-reader, but it’s such an epic and intimate book, I think it warrants it.

This year I also read everything Keigo Higashino has written that’s been translated into English. His Detective Galileo series is fantastic mysteries, but I absolutely loved his book Newcomer, which I’ve recommended to friends and family and described as Olive Kitteridge meets Columbo. And the way he subverts mystery tropes in Malice also made it one of the most fun reads of my year. Now to learn Japanese so I can read his other fifty-seven novels!

—Sarah (Production Manager)

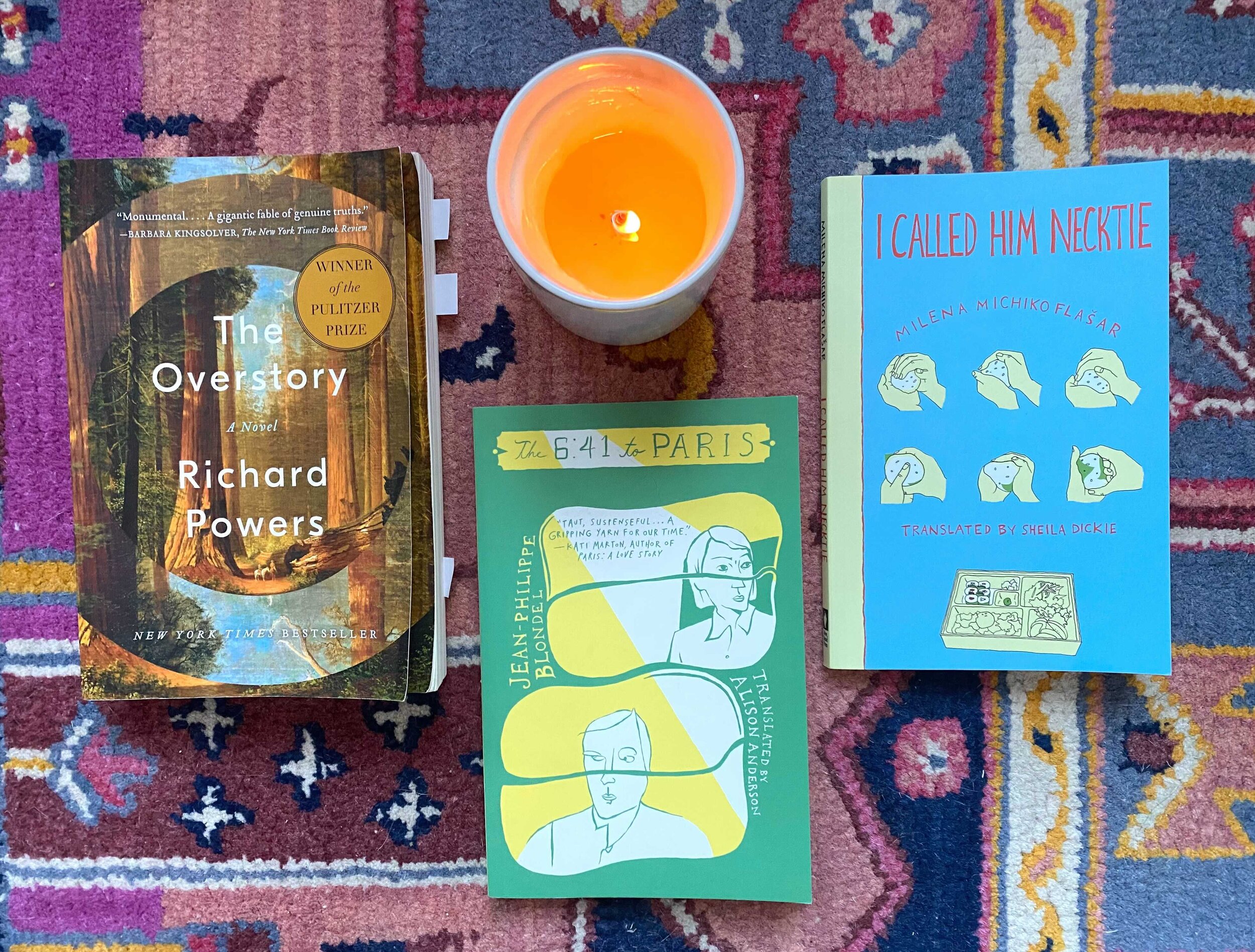

Two years ago, my first fall in New York, I picked up two novellas from the Brooklyn Book Fair, Milena Michiko Flašar’s I Called Him Necktie, translated from the German by Sheila Dickie, and Jean-Philippe Blondel’s The 6:41 to Paris, translated from the French by Alison Anderson. Although quick undertakings, I savored each one, especially Flašar’s sincere story of a twenty-year-old hikikomori reentering the world after two years of living without human interaction in his parents’ Tokyo home. Since lockdown descended in March, Flasar’s meditation on how we disconnect from life and what we need before we can embrace it again has given me so much solace. Both having been fixtures of my college dorm room, it felt simultaneously like a transgression and a gift to read them for the first time back in my childhood home.

Richard Powers’ The Overstory also blew me away. His book unveils a whole new way of attending to the living world. I defy anyone to read this book and not be left wanting to kneel at the foot of every tree they pass and weep at the majesty of these beings. A must-read for anyone interested in environmental fiction.

—Elisabeth (Intern)