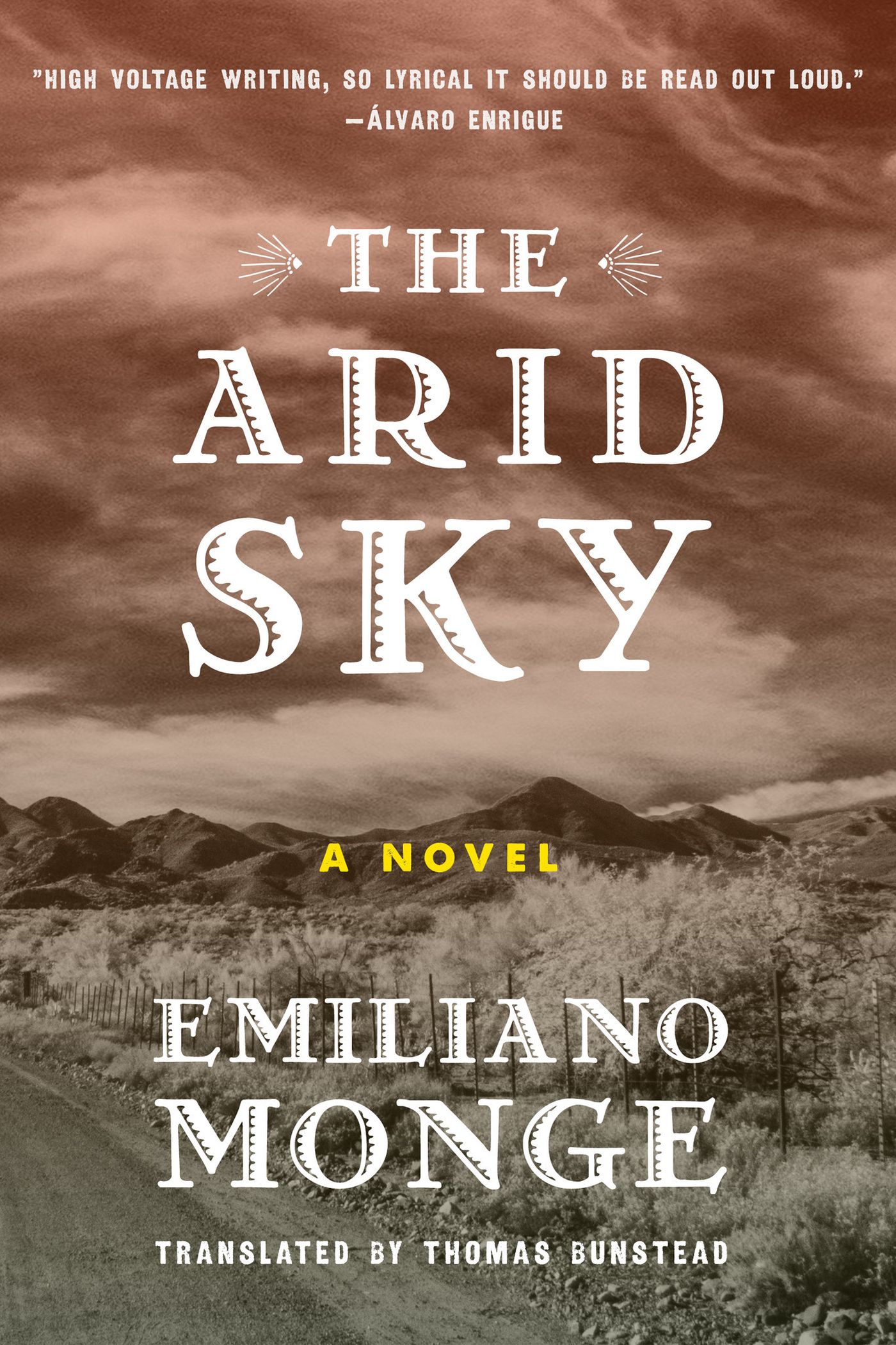

Get your hands on The Arid Sky, the novel the Los Angeles Times describes as a "stellar English-language debut" for author Emiliano Monge. Praising the novel's "bleak, lyrical prose" that "thrives on a persistent feeling of universality," reviewer Mark Athitakis writes "[The Arid Sky] evokes a sense of terrible acts constantly repeating in one place, history grimly folding back on itself. It’s a traditional western cut up and turned into an M.C. Escher print."

Read the full review here and grab your copy of The Arid Sky here.

Can’t wait for your copy to arrive? Get your first look at The Arid Sky with the following excerpt.

DISAPPEARANCE, ESCAPE

May 27, 1911, and another knot in our account of this life—a knot in which, at the hour when the sun beats down on the backs of men across the Mesa Madre Buena and the earth succumbs to the drowsiness and slowness that succeed spring, Germán Alcántara Carnero hears a sudden whistle and stops swinging his mattock. Puzzled, ourman, still a boy at this point in our story, turns and gazes over his shoulder, and when the whistle cuts through the air again, the three mangy dogs that were sleeping on the ground nearby rouse themselves, sniffing the air for a smell that is yet to reach the boy—the smell of a smudge coming down over the scrubland, where the heat from the earth meets the heat dropping from the incandescence that is the sky at this time of year.

He looks at the horizon, which is very clear, and sees the smudge as it continues to advance over the scrub. It’s been so long since we’ve had any kind of wind, thinks Germán Alcántara Carnero. Two, maybe three weeks and not the tiniest gust, he thinks, casting his mind back as the smudge continues its approach, gradually growing into a silhouette. The whistling man whistles again, calling to attention the men, women, and children hereabouts, who all leave off their work and, like Alcántara Carnero, stand and wait. The local landowner—the lord and master, that is, of these lands and of all the people in them—approaches on his mare, a thousand swirling starlings following in his wake. A solitary cloud crosses the sun—brief respite for Germán Alcántara Carnero as he wonders what orders they’re about to be given.

The cloud’s fleeting shadow, as fleeting as the words I am writing here, moves across the plowed field, across the plots in which seeds have already been sown, and then over the path along which the horse—whose glinting owner we will refer to as lordandmaster—is trotting. Eye drawn by the glints coming off of lordandmaster’s clothes, ourman—whom we will be better off calling ouryoungman, though in truth he isn’t even quite a young man yet—does not notice his dogs rousing themselves until they set to barking. “Quiet, you three!” he says as the lordandmaster whistles again. But the dogs continue to bark and whine, and, leaning down, he kicks one of the beasts in the neck and the other on the snout: “I said quiet!”

A little way off, ouryoungman hears someone asking: “What’s he want?” It is the man who always speaks up when anything happens in these parts: “What is it this time?” Another peon, a few meters from us, answers with a laugh: “He’s come to hand out some presents.” All those in earshot laugh. “He’s here to give us his horse.” And the first man, plunging his machete into the soil and wiping his brow, says: “I bet he’s going to tell us to all go home. I know him, and I know he don’t like being out in the hot sun like this…Bet he’s going to tell us, ‘Whoever doesn’t stay home will pay…’ Look at him, so sure of himself—cock of the walk!”

Lordandmaster whistles once more—not because any of his workers haven’t heard him already, but simply because he can, and because he knows it annoys these men.

“He’s frightened it’ll start here, too!” says the man who has begun exhorting his companions. “Frightened we’ll rise up as well. Bet you he’s going to come and complain about those ten men, and warn us off joining them.” “I wish he was afraid!” says one of the older men—the one who’s been working for longest on these lands, lands where the punishing heat even seeps through the ground, quickly fermenting any recently buried bodies. The man who spoke first, undeterred, indifferent to the old man’s reply, takes three steps forward and says: “He’s come to say, ‘woe to those thinking of welcoming them into their homes.’” But again, ouryoungman doesn’t hear this. He has just noticed a strange insect crawling from the ear of his dog and trying to pick it off. Seeing its blue-green wings, Germán Alcántara Carnero thinks: It’s a Jerusalem Cricket. I’ll give it to María, she’ll like it. He reaches out a hand, but then feels a sharp pain, a heavy blow that, though it doesn’t touch him, cuts the insect in two and therefore hurts him nonetheless. “That bug don’t bite, but he does!” says one of the peons as he comes by, pointing to lordandmaster at the far end of the field. “Better get over there now.”

Germán Alcántara Carnero watches in anger as the man, the machete in his hand, walks grudgingly over, but then falls in behind him. When he reaches the group surrounding lordandmaster, he catches the tail end of a phrase: “…I will go and seek them out, personally, and I will find them, and I will mete out such punishment on each and every one.” With his outsize hands, Germán Alcántara Carnero forces open a space between the men, who now turn their heads to the north, where the man who killed his insect has begun speaking: “So go back to our houses, is that it? And once we get there stay put? I have a better idea—why don’t you and your family go to fuck?” The men, though already silent, fall quieter still, and ouryoungman braces himself: lordandmaster immediately crosses the circle, his hand reaching for his gun, which he levels at the man’s head and, still advancing, pulls the trigger. And the man who killed the insect is blown onto his back.

The mouth of the fallen man issues the final gurgling sounds that his body will ever emit, as though his heart and lungs, before giving in, had to unleash a final insult to the workers looking on in silence, heads bowed, waiting for their next order. “Home,” roars lordandmaster, “all of you get home, and don’t let me catch any of you going out.” They all stare back at him, all except for Germán Alcántara Carnero, who is watching the hole through which the dead man’s brains are dribbling out. “Don’t none of you come back out again till I say so.” And with that, lordandmaster mounts his mare once more and, pulling hard on the reins, shouts: “Don’t let me hear that any of you have been talking with the Rio Verde men, nor showing them any kind of hospitality.” Pleased with their silence and with the obedient turning and walking away of his workers—men who, even with their backs to him, don’t dare to defy him in words or thought— lordandmaster spins begins moving off, but then ouryoungman’s dogs begin barking again and he turns back. What’s Félix’s boy doing now? he wonders, with confusion that will soon produce a smile on his face. What’s he doing peering at the dead man? Is he really going to…? Nodding his head, captivated, lordandmaster lets out a laugh as he sees the person who will one day be ourman reach out and thrust his outsize fingers into the bloody wound. Lordandmaster, up on his mare, applauds, saying to himself: This you’ll never forget, not this, Félix’s little boy, before tugging on the reins again and setting off. The surprise on the face of ouryoungman—the only worker remaining—lingers: he has seen dead men before but never gone so far as to touch one, and never imagined the blood would be this warm. Crouching, looking in the dead man’s eyes, he whispers: “That’s what you get, fucker, for hurting my beetle. It was meant to be a gift.”

He looks up, the only things around him now his three dogs and the vultures that have just landed a little way off—beyond them across the fields he can see the diminishing silhouettes of the workers picking their way through the scrub, and beyond that the rocky outcrop, sandstone winking in the sun, and beyond the rocky outcrop the vast swath of thicket land where his family lives and where a dam will one day be erected.

Picking his way across the fresh furrows to his mattock, he gathers it up along with the two halves of the beetle that crawled out of his dog’s ear, and thinks of his sister, who turns fourteen today and who has never uttered a word in her life: she was born with a tongue the wrong size for her mouth. “I’ll find her something else. By the time I get back to the house, I swear I’ll have another present.” Scanning the horizon once more, ouryoungman enjoins his dogs—who are casting resigned looks at the fly-covered corpse also being contemplated by the jumpy vultures: “Come on, you three. Let’s go!” Leaving the field behind and passing up and down a number of small knolls, he cuts into the part of the land where at certain times of the year beanstalks and at others alfalfa and sorghum and grass and corn grow, in haphazard manner: a manner replicated by almost everything on this plain and thus by this story as well. Here a hundred shoots, there a group of stalks and the heads of some maize, and over there, corncobs in an unlikely line. Here the earth begins to change: the weeds begin to break up into discrete clumps, drifting farther apart and soon coming to resemble islands and then finally small islets charting a course in an ocean of earth—on the surface of which the stone just thrown by Germán Alcántara Carnero lands.

Without breaking stride, ouryoungman leans down and plucks another stone from the path, cleaning the soil from it as he did the previous stone—spitting on it and rubbing it with both hands before carefully checking it over and then hurling it angrily toward the horizon. He has no choice but to find a new gift for María del Sagrado Alcántara Carnero. On this part of the path we are on, where the soil turns sharp and rough underfoot and even the islets of clumped grass desist, the boy who will one day be ourman is more likely to find the surprise he’s looking for: a stone with a fossil inside, one that shows how this area was submerged beneath water in epochs past. He bends down, picks up another stone, checks it, discards it. At the point the path exits the stretch of seemingly ravaged lands and enters the area that precedes the rocky outcrop we are very soon to arrive in—a place where the ground resembles leprous skin—Germán Alcántara Carnero leans down again and, picking up a fourth stone, smiles and gives a small excited skip. Finally, a good gift.